The Story of an Oregon School Bombing

1895 – 1901

by Stephen Williamson

© 2005, 2023

Download the full PDF including references here.

On a hot July night in 1901, in the small community of Mohawk, Oregon, a school named Ping Yang was blown up by a bomb. It was the third bombing of the school since 1895. (1) Each of the attacks was at night and no one was injured. The bombings were widely reported in Oregon newspapers, but no one was arrested.

Why was an Oregon school named “Ping Yang” – an Asian name? Why was it bombed three times and set on fire twice? The answer is a complex mix of social, religious and racial tensions that exploded in the small, rapidly growing community. According to the 1900 US Census and news articles, Mohawk had almost 700 people and at least 150 were Japanese and Italians. They mostly worked on the railroad and in lumber camps. (2)

This July 20, 1901 Eugene Weekly Guard newspaper does not name the “fiend who is so bent on demolishing the building.” Several news items tell of “certain parties” who were known, but solid proof was lacking. Articles written in the 1960’s said it was likely the work of “Old Joe” Huddleston, a longtime resident. He is said to have named the area “Ping Yang.” Huddleston was one of the most powerful men in the Mohawk Valley.

Over the decades several myths have been fashioned to explain the bombings and their significance. Little has been written about the attacks for over forty years.This article is an update to my 2005 report. It was the first attempt to put together a timeline of events to understand why the school was bombed and why no one was arrested. The Ping Yang School bombings may be one of the biggest unsolved crimes in Oregon’s history.

NOTE: Pyongyang is the actual name of the Korean city that Americans called Ping Yang.

Oregon’s Mohawk Valley was named in 1849 by an early immigrant, Jacob Spores.(3) He said it looked like the Mohawk Valley in New York State. The new White immigrants soon began to call the Native Kalapuya Indians “Mohawks.”

However, by the Spring of 1895 a new school in the valley was being called “Ping Yang,” so named by Joe Huddleston.(4) Why did he choose that name? Why did the community accept it? In 1894 the name of Ping Yang became known all around the world. A huge battle was being fought in Korea by Japanese and Chinese armies.

Oregon’s Ping Yang was locked in a battle over the new school. Mohawk Valley residents were arguing over its location partly because it could determine the future location of Lane County roads and railroads. Whichever side of the Mohawk River was chosen could be the fastest growing and its land more valuable.

Ping Yang was about 12 miles northeast of Eugene where the community of Mohawk (also called Donna) is today. A driving tour map of the area is at the end of this article. The Ping Yang School stood across the road from where the historic Mohawk Store and the Mohawk Community Church are today.

The Ping Yang School had been built to relieve overcrowding in nearby schools. The valley was growing rapidly. While there is no evidence that Asian children were ever taught there, it is very possible that missionaries were using the school to teach Asian railroad workers both English and Christianity.

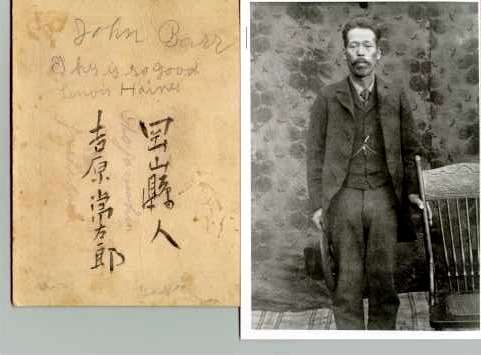

The school was used by several religious groups. One Japanese man gave his photo to a White friend writing the words “thy is so good” on the back. He likely learned English from a teacher using the King James Bible. His picture and home address in Japan are below. Above is a picture from about 1905 of a Japanese railroad crew in Marcola.(5)

1895 – Attacks Happen When School Opens

Controversy happened as soon as the Ping Yang School was built. The Mohawk School District had broken itself into four separate, smaller districts.(6) What had been one school district with four schools became four districts with four school boards.

At that time, children were expected to walk up to three miles each way to school. These schools were less than three miles apart but separated by the river and creeks. For whatever reasons the Mohawk School District divided itself with each school in its own district.

By early 1895 the new school was named “Ping Yang.” Some parents worried their children would have to cross the dangerous river and creeks on little foot bridges. It is possible that the first bombing was supported by residents on the East side of the river because they wanted the school on their side. West side parents felt the same way.

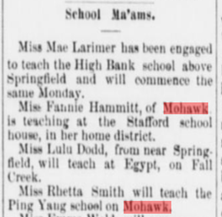

On April 13, 1895, the Eugene City Guard stated, “Miss Rhetta Smith will teach the Ping Yang School on Mohawk.”(7) But she only taught for two weeks before it was bombed!

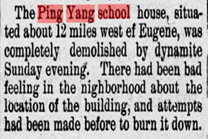

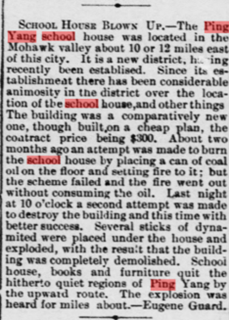

The Dalles Times-Mountaineer wrote on April 27, 1895 (8) “The Ping Yang school house, situated about 12 miles west of Eugene, was completely demolished by dynamite Sunday evening. There had been bad feeling in the neighborhood about the location of the building, and attempts had been made before to burn it down.” (Note: Ping Yang was 12 miles EAST of Eugene)

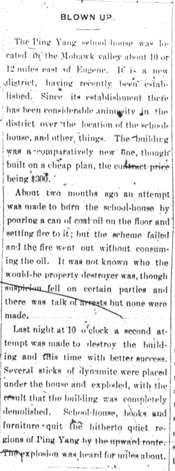

An Albany newspaper article from May 3, 1895 (9) says that the Ping Yang School was bombed because of fights over its location and “other things.” It also reports the school was the target of two fires and that the dynamite explosion was “heard for miles about.”

The Highbinders

People Who Supported The School

A few years later, Joe Huddleston is said to have created his own homegrown version of China’s Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901). He used racist anti-Asian imagery to campaign against the school.

He called himself and his followers “Boxers” and people who supported the school he called “Chinamen” or “Highbinders,” (10) a slur word for the way some Asian men wore their hair.

Rising to save the school were a group of ordinary people who believed in public education. They were farmers like the Haydens, lumbermen like John Barr, teachers like the Hammitt, Spores and Stafford families, and merchants like Columbus Cole and Marvin Hammitt.

One of the area’s teachers, Maude Kerns, later became a University of Oregon professor and known for her work with Asian art. 11) A fiery old pioneer preacher named John F. Mulkey helped build the school and led the fight to keep it. (12) Here is a photo of Reverend Mulkey and his wife. A news story of the first bombing in 1895 is above. (13)

Like many rural schools at the time, Ping Yang was a small schoolhouse with just one classroom that measured twenty-five by thirty feet and was built of logs. (14) It cost $500 to build. Most early rural schools also served as public buildings. Ping Yang was used as a church by several religious congregations and also for civic meetings.

Another bombing, several years later, blew a hole in the classroom floor. A former student later remembered that the teacher “instructed her class skirting the edge of a large hole in the floor.” (15) The school was bombed for a third and final time in 1901. Community members repaired the school after each attack. Both the 1895 and 1901 news stories say that suspicion points to “certain persons” but there was “no tangible proof.” (16) The July 20, 1901 Eugene Guard shows the long battle over the school.

Joe Huddleston and his followers are mentioned in later articles about the Ping Yang School – but neither he nor anyone else was ever charged with a crime. In fact, Huddleston was elected Mohawk’s Constable, Justice of the Peace and Mayor. The Eugene City Guard called him the “Republican Boss of Mohawk.”

The issue of building and keeping the Ping Yang School deeply divided the Mohawk area. What was so controversial about building a new school in a growing community? What made this school so controversial that townspeople were able to stand by, and in some cases, even participate in the bombings? Very few schools cause enough uproar for three bombings and two fires to happen – with zero arrests.

A “Devil’s Lane” Divides Feuding Neighbors

In the Fall 1970 Lane County Historian, Claud Hammitt says that “Mohawkers did not always get along. If adjoining neighbors developed a bad enough feud, sometimes they wound up by putting in a “devil’s lane.” This was two fences running parallel between their land with a “no-man’s” strip in between. But that solution did not necessarily end the feud. Often, more friction developed between the neighbors. Each one watched the other; a fellow had better not let his cattle graze on more than half of that “neutral” strip.

“Joe Huddleston, who always loved a good fight, also had one. The man on the other side of Joe’s got religion and suggested that they bury their differences and do away with one of those shameful fences. Joe, who liked making friends as well as he enjoyed enemies and a good fight, agreed. But he did not realize his Christian “saved” neighbor had other plans. He intended to take down the fence on his own side, thus adding the entire strip, the “devil’s lane,” to his property. Back went the “devil’s lane” and the feud was revived.” On page.56, Hammitt says Joe was for “all out war on the new school.” (17)

It’s largely thanks to historian Claud Hammitt and his articles that we know something about Joe Huddleston and these events. Claud Hammitt attended school at Ping Yang (also called the Hammitt School). His family built the Mohawk General Store and the school. He wrote articles for the Lane County Historian and other publications. Claud Hammitt had lived near Joe Huddleston for many years and knew him well.

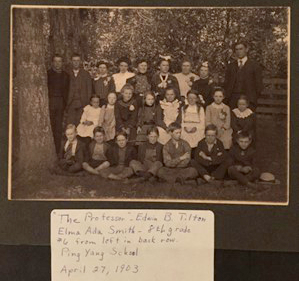

A Ping Yang School Class

This picture is from April 27, 1903, two years after the final bombing. It shows the students and their teacher outdoors.

The school was still being called Ping Yang. Unfortunately, It does not show the school building. They called their teacher, Edwin Tilton, “The Professor.” (18)

Critics try to use this photo to say there were no “Orientals” (their term) at the school. But no one has ever suggested that Asian children were taught at the school.

However, the Ping Yang School may well have been used by local missionaries to teach the many new Japanese railroad builders how to speak English using the King James Bible.

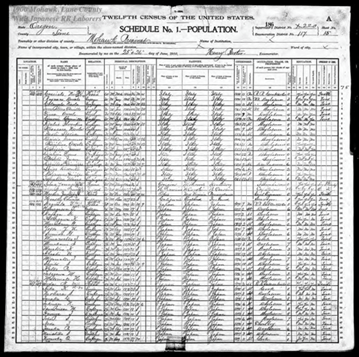

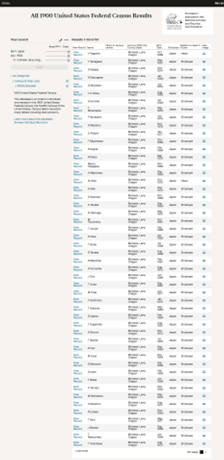

It’s been claimed that Mohawk had only a handful of Japanese during the school troubles. However, below on P. 28, see the 1900 US Federal Census that shows 50 Japanese (and also many, mostly Catholic, Italians). A newspaper story from April 1900 shows 150 railroad men, half Japanese and half Italian. Minorities were there.

1895 – Why Name the School Ping Yang?

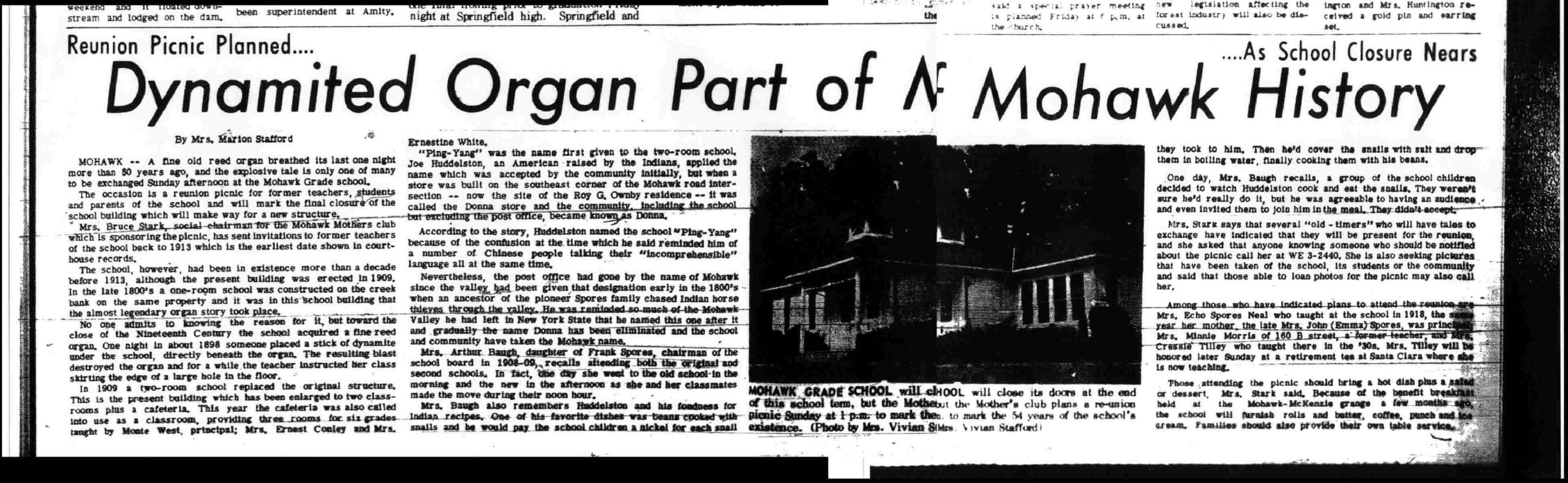

There are several interesting tales of how Ping Yang got its name and why it was bombed. But these stories were not written until many years after the bombings.

Here are some of the reasons reported for the origin of the name Ping Yang. According to newspaper reports, the name “Ping Yang” belonged to the area, not just to the school. A number of newspaper reports from 1895-1901 use the name of Ping Yang to refer to the geographic area. (19)

One story says Joe Huddleston named it Ping Yang because he did not like the sound of school bells. The bell reminded him of a railroad bell clanging “ping yang … ping yang.” He said that the school bell woke him up too early in the morning. (20)

Another story says that Old Joe named the school Ping Yang because students playing on the school grounds sounded to him like a bunch of “Chinese people talking their incomprehensible language all at the same time.” (21) He disliked kids’ playground noise.

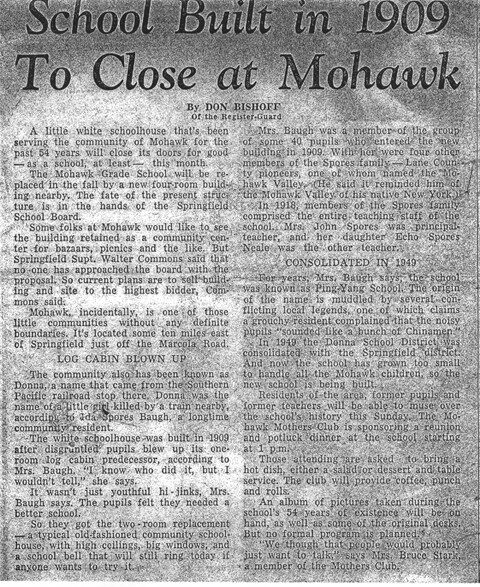

Perhaps the most interesting motive for the bombings was told to Eugene Register Guard reporter Don Bishoff in 1963 by Ida Spores Baugh. She had attended the school and her parents taught at the Mohawk School, built in 1909 to replace Ping Yang.

Mrs. Baugh stated that “disgruntled pupils” blew up the school! Mrs. Baugh also said “I know who did it, but I wouldn’t tell. It wasn’t just youthful hi-jinks, the students felt they needed a better school.” (22) This story certainly adds a new twist to school pride.

Who Gave Students Dynamite?

It’s also possible some parents were involved or that the school, having been bombed twice, was in poor condition.

In 1894 there was a news story on young people being influenced to carry weapons by unnamed “certain parties.” Youth are often attracted to colorful elders. Huddleston was also known to sometimes use dynamite for fishing by blasting the fish out of the water. (23)

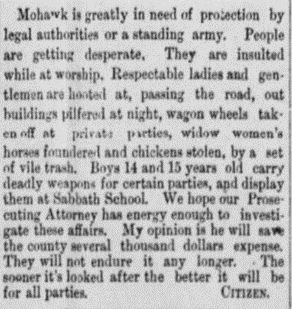

1894 – Boys Carry Deadly Weapons for “Certain Parties”

A Eugene news article from March, 1884 tells of boys carrying weapons and harassing people. It says that Mohawk needs more law enforcement. An unknown local writer calling themselves “Citizen” says:

“Mohawk is greatly in need of protection by legal authorities or a standing army. People are getting desperate. They are insulted while at worship. Respectable ladies and gentlemen are hooted at, passing the road, out buildings pilfered at night, wagon wheels taken off at private parties, the widow women’s horses foundered, and chickens stolen, by a set of vile trash.”

“Boys 14 and 15 years old carry deadly weapons for certain parties and display them at Sabbath School. We hope our prosecuting attorney has energy enough to investigate these affairs. My opinion is that he will save the county several thousand dollars expense. They will not endure it any longer. The sooner it is looked after the better it will be for all parties.” (24)

The Ping Yang Band

In 1901 the Southern Pacific Railroad renamed the community Donna, in honor of a small child who was on the tracks when one of the first trains passed. (25) The railroads changed many local names to make them easier for train personnel to pronounce and write down. But the local community continued to use the name of Ping Yang for years.

The nearby town of Isabel was changed to Marcola (after Mary Cole, wife of Columbus Cole, an early merchant in the valley). (26) While the name of Ping Yang ceased being used for the village, people continued using the name for years. Here is a 1914 photograph of the Ping Yang Brass Band with fourteen members holding their tubas, trombones, trumpets and drums. (27) Another controversy about the Ping Yang School was that it was also being used for dances. Most schools had multiple uses, but dancing was frowned upon by many people. Dances also make noise.

Why would a community allow a few individuals to destroy a public school? They kept rebuilding it, but none of the accounts tells why local people were willing to see it bombed three times. A few people’s dislike of its location, playground noise, school bells or dancing does not seem enough reason to tolerate three bombings.

If Joe Huddleston wasn’t one of the instigators behind the attacks, as a community leader he was certainly in a position to help stop them. Huddleston had many followers and held several public offices. He had lived in the community for decades and despite later being elected Constable and Justice of the Peace, he did not find the criminals.

1894 – The Storming of Ping Yang, Korea

Where did Joe Huddleston get the name of Ping Yang? The best explanation of how it got its name is in a 1966 article by historian and Mohawk resident Claud Hammitt. His family operated a general store near the school. Ping Yang School was also known as the Hammitt School. (28)

Claud Hammitt knew Joe Huddleston most of his life. Huddleston was a neighbor of his family’s store. In the April 1966 issue of The West Magazine, he writes that Huddleston named it for one of the “Chinese battlefields.” (29) Hammitt wrote his articles after the 1963 reports of the Mohawk School closing. He had attended both schools.

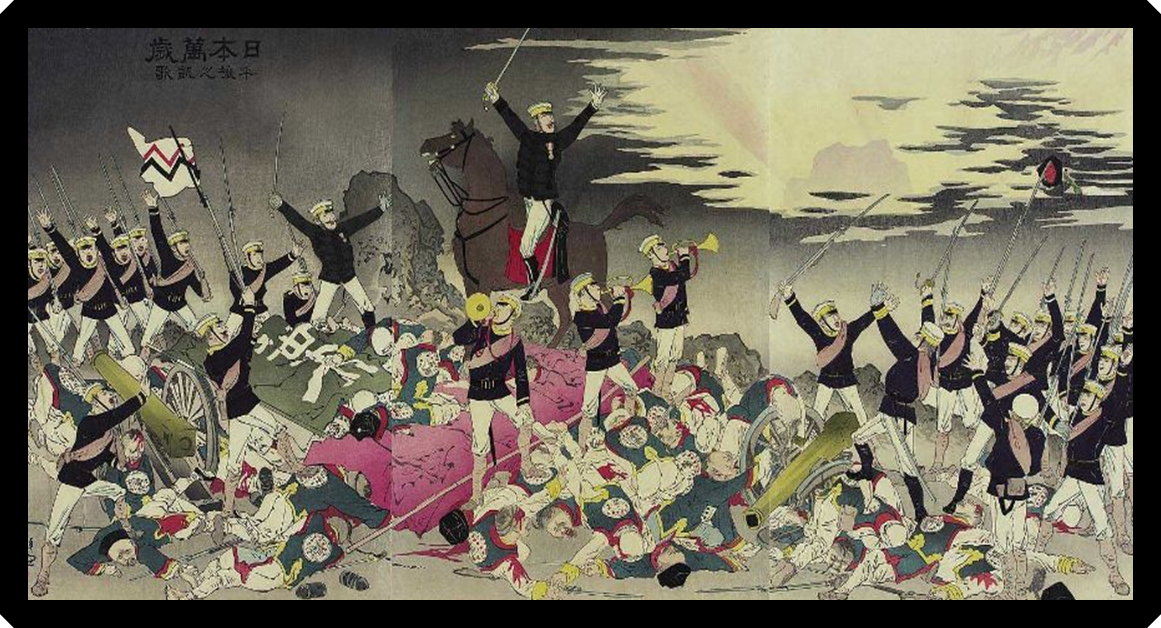

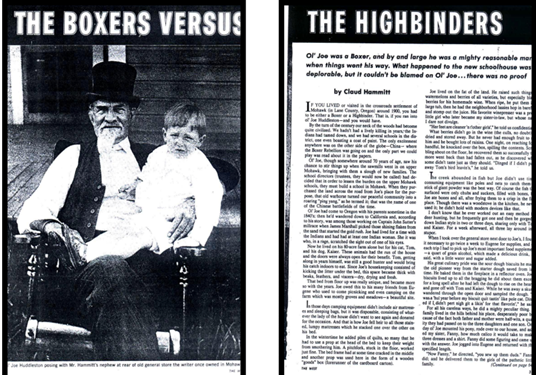

Hammitt’s article, titled “The Boxers Versus The Highbinders” describes Huddleston’s efforts to rally the community against the school. The “Chinese battlefield” was actually near Korea’s capital city. The source for the name of Oregon’s tiny schoolhouse comes from the Battle of Ping Yang in Korea fought in 1894 between China and Japan.

Ping Yang was the capital of Korea and still is the capital of North Korea. Its real name is Pyongyang, but few Americans could spell or pronounce it. In September of 1894, Japanese forces invaded Korea to drive out the Chinese who were believed by the American public to be persecuting the Koreans. One of the most widely read news correspondents was James Creelman. He was in Korea and wrote rousing descriptions of the battle glorifying the Japanese and condemning China. Here is art from the battle.

James Creelman’s popular international dispatches were read all over America and Europe. He had interviewed President McKinley, the Sioux Indian leader Sitting Bull, the Russian author Leo Tolstoy and the Pope in Rome. He wrote for William Randolph Hearst’s newspapers and also covered the Spanish American War. (30)

A full account of Japan and China’s battle for Korea is beyond the scope of this article, but some background knowledge is important to understand what happened in Oregon. American news reports of the battle presented the Japanese as heroes and liberators of Korea from the Chinese, who were portrayed as cruel invaders by Western newspapers.

One paragraph from James Creelman’s news story “The Storming of Ping Yang” captures the flavor of his writing – and the American preference for Japan over China. The entire news report can be read online from Google Books.

“The armies of Asiatic barbarism and Asiatic civilization met on this ground to fight the first great battle of the war; and here Japan emancipated the helpless Corean nation from the centuried despotism of China.” (31)

As a result of James Creelman’s war dispatches, the name of Ping Yang was associated very positively with Japan and helped immigration to the United States. It would be logical to use this positive association if the goal were to increase acceptance of Japanese workers over Chinese. Huddleston may have named it to get people to allow seasonal Japanese laborers. That could be a reason the community accepted the name of “Ping Yang.” Chinese were the villains at the time.

Perhaps Huddleston chose the name simply because Mohawk residents were already in a battle over the school’s location. The school’s location is mentioned in news stories. But was the location by itself controversial enough for a community fight?

April, 1895 – The First Bomb

Within months of the battle of Ping Yang in Korea, the first blast in the battle of Oregon’s Ping Yang was fired. The story of the first bombing is preserved in a Florence, Oregon newspaper article from May 3, 1895.

The article notes that it was a new school and that “there has been considerable animosity in the district over the location of the schoolhouse, and other things.” The article also tells of the first attempts to destroy the school by fire and that more than one person was suspected of the crime.

“About two months ago an attempt was made to burn the school-house by pouring a can of coal oil on the floor and setting fire to it; but the scheme failed, and the fire went out without consuming the oil. It was not known who the would-be property destroyer was, though suspicion fell on certain parties and there was talk of arrests, but none were made.

“Last night at 10 o’clock a second attempt was made to destroy the building and this time with better success. Several sticks of dynamite were placed under the school and exploded, with the result that the building was completely demolished. School-house, books and furniture quit the hitherto quiet regions of Ping Yang by the upward route. The explosion was heard for miles about.” (32)

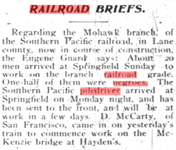

The community rebuilt the Ping Yang School, and it ran without much trouble for the next several years. The second bombing happened in 1900. This is when newspaper articles show a number of “negroes” and “Japs” coming to work on the railroad. (33) News articles show community fights over the location of the new railroad and the huge Booth Kelly lumber mill at Wendling that was changing life in the Mohawk Valley.

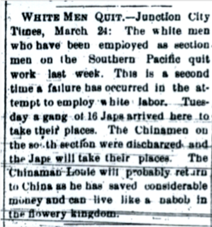

“White Men Quit” – Why Japanese Came To Oregon

Japanese immigrants were brought to work on Mohawk Valley railroads. It was difficult to get Whites for the work as told in a news article titled “White Men Quit” from March 26, 1900. (34)

The story says that Japanese are being employed because the community would not accept Chinese workers. White men did not want to do the hard, low paying labor. Better jobs were available in the timber industry. But Japanese crews built good railroads.

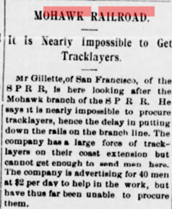

The battle for Ping Yang, Korea made for very good public relations for the Japanese. Japan kept track of its immigrants in America. Japanese officials in America sent back detailed reports about how the Japanese could prosper here. One report, sent to the Meiji Foreign Office from Idaho, states that the battle of Ping Yang had made White people more favorable to the new Japanese immigrants. A July 21, 1900 article also reports the dire need for railroad track layers.(35)

The Meiji report shows the importance of the battle of Ping Yang in changing American’s views of Japan.

“When railroad construction began four years ago, hostile Whites attempted to force the Japanese out, but these threats soon subsided. At the same time the victory in the Sino/Japan War caused many Whites to change the way they viewed the Japanese.” (36)

While most people wanted a railroad through their community, a few did not. A railroad meant progress and rapid population growth. Joe Huddleston was over sixty years old when the railroad came to Mohawk. A railroad meant the end of pioneer life and an influx of people from all over the world – with lots of noise.

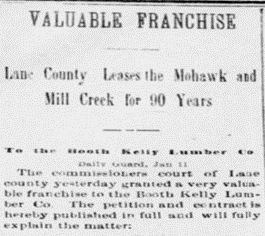

1899 – More Fights – Mohawk River Leased Out

In 1899 another controversy struck the community. Lane County gave the large Booth Kelly Lumber Company a 90 year lease for control of the Mohawk River. The river is called a “Valuable Franchise” in the January 14, 1899 Eugene City Guard. (37)

The article says that the corporation was granted all the rights and interest of Lane County over the Mohawk River for 90 years. This was a shock to residents and divided them further. Public meetings were held, and citizens protested, but the decision stood.

One newspaper said that locals were in favor of the lease, while another article said that residents opposed it. A small publication, the Broad-Axe, suggested that some papers might be accepting “hush money” from the logging company to not cover the story. (38)

The new railroad line, carrying a seemingly endless stream of people and lumber, was built right across the road from Joe Huddleston’s house. The Mohawk Valley was home to some of the richest timberlands in the nation. The Booth Kelly Lumber Company would soon employ hundreds of men in the nearby community of Wendling. (39) Lumber mills were springing up on almost every creek. The railroad made the valley grow.

The bombing of the Ping Yang School may have been partly in reaction to the rapid industrial growth of the Mohawk Valley and the hundreds of families coming for jobs. Huddleston campaigned against the school using racist images. Most Americans did not recognize the different Asian nationalities. Whether Korean, Japanese or Chinese, most male Asians were simply called “Chinamen.”

Then, in 1900, an event happened in China that was to give the campaign against the school new life and lead to more attacks…

1900 – 1901 The Boxers Vs. The Highbinders

In 1900, Joe Huddleston and his followers organized their own homegrown version of China’s Boxer Rebellion. As reported in Claud Hammitt’s 1966 article, “The Boxers Versus the Highbinders,” (40) China’s Boxer Rebellion was making headlines. Groups of Chinese monks trained in martial arts wanted to throw out all the foreigners from China and regain control of their country. They killed hundreds of Christian missionaries and their Chinese converts. Westerners had seldom seen martial artists and called them “Chinese Boxers” because they had no other name for the warrior monks.

The popular writer Mark Twain supported the Boxers in driving out foreigners from China. He called himself a Boxer and favored driving the Chinese from America. He also opposed imperialist intervention in China and is a popular writer there today.

A widely publicized speech of Mark Twain’s in 1900 contains his famous “Boxer” quote:

“China never wanted foreigners any more than foreigners wanted Chinamen. The Boxer believes in driving us out of his country. I am a Boxer too, for I believe in driving him out of our country.” (41)

“Old Joe” Huddleston – Leader of the Mohawk Boxers

Joe Huddleston was a legend before the bombings. It is said he told many tall tales about himself. But, he was also able to speak Native American languages and cook their recipes. Huddleston had come West in the 1840s and he had lived among Native tribes. He was called “Old Joe” by many people. Huddleston was a crack shot with a gun. Old Joe also had his unique way of fishing using dynamite to blast out dozens of fish at a time. (42)

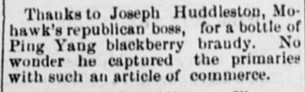

Huddleston was also his own publicist. Newspapers would run stories he told. News articles have him selling blackberries, watermelons, fish and Ping Yang Brandy. He also mined gold in his youth and traveled around the West.

The Feb 12, 1881 Oregon Sentinel (43) shows both his hunting and storytelling skills. He claimed to have shot 38 deer with 37 shots – killing two deer with one shot! He also told the Eugene City Guard on July 18, 1885 (44), that he was going to sell blackberries for 12 ½ cents per gallon. It was good advertising, and the papers seemed to like his tales.

There is no definite proof Huddleston was behind the bombings. He was suspected at the time. He likely condoned them or he could have had the real bomber(s) arrested. At various times Joe Huddleston was elected Mohawk’s Constable, Judge and Mayor.

If Huddleston had no role in the bombings and did not know who was doing them, then it seems like he would have been quoted in one of the newspapers. He probably would have wanted to know who was repeatedly blowing up a school across the road from his house. If Huddleston had wanted someone arrested, they likely would have been. It’s hard to imagine he could not catch at least one of the bombers (voters) if he wanted to.

Huddleston was apparently well educated – but did not want a school close to him. He is not known to have ever been married. Claud Hammitt reports that he drank strong grain alcohol frequently and one of his eyes was badly scratched in a fight with a woman. (45)

But there was also another side to Huddleston that his friends and supporters saw. He could be very kind and helpful to people in need. There is one report of him having had clothes made for a very poor family whose parents were mentally retarded. (46)

Joe Huddleston was clever enough to manipulate citizens’ fears of the school and new immigrants. According to Claud Hammitt, if you sided with Huddleston and his followers you were a “Boxer” — but if you were against him, you were a “Highbinder,” a racial slur.

Huddleston’s avowed foe, the Reverend John F. Mulkey, wore a long beard and tied it behind his back while working on his farm. Huddleston ridiculed him, calling the old minister a “Chinaman” and a “Highbinder” for the way he wore his long beard and his support for the school. (47) John F. Mulkey was also from a pioneer family. The Mulkey family had produced preachers for the Church of Christ faith. (48)

Claud Hammitt’s article in The West Magazine pokes fun at Rev. Mulkey calling him a “little sawed-off man with a beard so long that he tied it up in a knot.” (49) Hammitt elevates Huddleston to a folk hero putting up “the good fight.” He praises Huddleston and mocks Mulkey. Claud Hammitt was a student at the school as a boy.

April 1900 – “Sixty Japs Coming”

In April 1900, the year of China’s Boxer Rebellion, sixty Japanese men immigrated to the Marcola area to build the long-awaited railroad. A Eugene front page news report proclaims in all capital letters: “SIXTY JAPS COMING” for the Mohawk Railroad. (50)

The June 1900 US Census on P. 28, shows 50 Japanese living in Mohawk More would soon come. It also shows many Italians, most of whom were Catholic. Oregon was very anti-Catholic at this time. This May, 1900 Mohawk news item (above) says, “about 150 of the men are Italians and Japanese.” (51)

April 1900 – Mohawk Railroad Workers Not Paid

Work went poorly on the first stretch of the Mohawk Railroad. The contractor went bankrupt and some of the workers did not get paid. This article on the left is from April 7, 1900 and says that “The Workers Are Without Funds and Destitute.” (52)

Work went poorly on the first stretch of the Mohawk Railroad. The contractor went bankrupt and some of the workers did not get paid. This article on the left is from April 7, 1900 and says that “The Workers Are Without Funds and Destitute.” (52)

The newspaper pleads with the community to help these men find work. The article also advocates for the Southern Pacific Railroad to pay the men for their hard work – which they later did.

“The men who have been working for Contractor Bays on the Mohawk branch of the Southern Pacific, deserve the greatest sympathy. Without money, after working all winter in the mud and wet, actually suffering in some instances for food, which they are compelled to get by asking for handouts, these honest toilers are in need of anything which can be given them.”

On the right is an article from the same issue with the headline “A Lien For Work.” (53) It says that the workers have not been paid since January (four months) and some had to sleep in the city jail!

These news articles do not mention the men’s ethnicity, but some were likely minorities. Whites could get good jobs in the timber industry. It was very difficult to get White workers to work on the railroad. The railroad was completed in 1901.

The Hayden Family Of Ping Yang

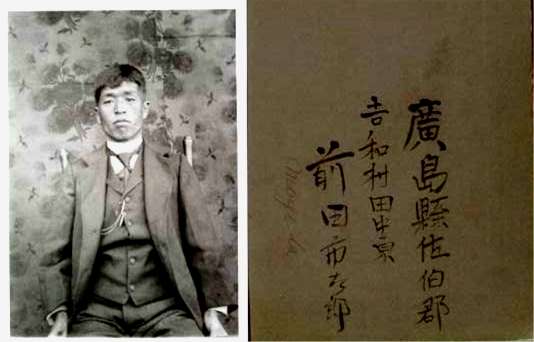

Two Japanese men became friends with a family named Hayden who were supporters of the Ping Yang School. Tsunezro Yoshihara and Ichizaro Maeda lived on the Hayden farm for at least a year. Maeda had his own garden of herbs and vegetables. (54)

The Haydens were poor small farmers but valued education highly. They had a good home library. Ella Hayden was an early University of Oregon graduate and was a schoolteacher for many years. Ella’s brother, Charly (correct spelling) was very interested in science, and also studied to be a minister and played the violin.

Because of them we have two very rare photographs of early Japanese in Marcola dressed not as laborers, but in their best American clothes. The Hayden’s interest in education may have been one reason they made friends with the Japanese immigrants.

Both photos below have the men’s home addresses in Japanese and were given to the Haydens when the men moved away from the Mohawk Valley. Charly Hayden’s grandson says he wrote letters to Maeda for years. Maeda and Charly were close in age, and both worked with the nearby railroad. Charly Hayden also helped pay for his sister Ella’s college education. Today a road, “Charly Lane,” is named for him.

Maeda And Tsunezro, Friends Of The Haydens

This photograph of Tsunezro Yoshihara is remarkable because written on its back is the phrase “Thy is so good.” He may have learned English from traveling missionaries who used a King James Bible with “thy” and “thou” words. He also printed the names of John Barr and Lenora Haines. Yoshihara’s home address in Okayama Prefecture is written in Japanese.

Here is Ichizaro Maeda. Someone printed his name as “Maydea” on the back of the photo. His address in Japan is also on the back and translated gives his address as: Tanaka Izumi Yoshiwa Saeki in Hiroshima Prefecture.

The relationship between the Haydens and these two men is unclear. However, the Haydens’ interest in education, the writing on the back, plus that they wrote each other letters, suggest they were more than just workers and renters. They were friends.

“We Have Got a Woman Preacher at Ping Yang”

Religious and Political Tensions Rise

Almost forgotten in later accounts of the bombings is that the school was used both as a church and for political campaigns. A 1963 article quoting former students says the bomb was placed under a reed organ (a small and portable organ). (55) Religious and political differences were another possible motive behind the bombings.

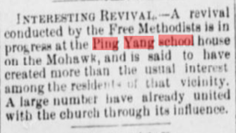

Early schools were often used as churches and for other public activities. This school was used by the Rev. John F. Mulkey for his services. Other church groups also met at the school. One of these groups, the Free Methodists were known for their strong opposition to slavery, support of prohibition and immigrants. They also allowed women to preach. Women in the pulpit is still strongly debated within Christianity today.

An article from the Eugene City Guard, dated August 01, 1896, shows the growth of the progressive Free Methodists around Ping Yang. (56)

“INTERESTING REVIVAL – a revival conducted by the free Methodist is in progress of the Ping Yang schoolhouse on the Mohawk and is said to have generated more than the usual interest among the residents of that vicinity. A large number have already united with the church through its influence.”

Prohibition of alcohol may also have been another motive. In both the 1896 and 1900 elections the school was used by supporters of Democrat William Jennings Byran for President. He was in favor of outlawing alcohol. It was a hot issue in both elections.

Joe Huddleston, a Republican, countered by running for public office and giving away bottles of Ping Yang Blackberry Brandy. This was less than a year after the first bombing. He won the election.

The June 20, 1896 Eugene news item about his Ping Yang Brandy reads: “Thanks to Joseph Huddleston, Mohawk’s Republican boss, for a bottle of Ping Yang blackberry brandy. No wonder he captured the primaries with such an article of commerce.” (57)

During both the 1896 and 1900 Presidential elections the school was used by supporters of prohibitionist William Jennings Bryan. The October 10, 1896, Eugene City Guard reported that “Attorney H.D Norton and C.M. Kissinger left this morning for Mabel precinct where they expect to make Bryan speeches this afternoon and tonight at the Ping Yang school house …” (58) The Presidential election of 1900 was a rematch between McKinley and Bryan, with McKinley winning again.

The Free Methodists originally formed to protest slavery in the United States. Free Methodists also ordained women as evangelists and supported their right to vote. By 1875 there were Methodist missionaries in China, Korea and Japan. There was also a Japanese Methodist Episcopal church in Portland that began at the turn of the 20th century. (59) The school was also being used by church groups like the Seventh Day Adventists.

Louis Polly’s 1984 book A History of the Mohawk Valley and Early Lumbering has a photograph of Japanese tea that Columbus Cole, an early merchant, imported and packaged under his own brand name. He sold “many items from Japan,” according to a video tape made by Louis Polley. (60)

Cole may have expected the local market for Japanese goods to grow from more immigrants. Another reason for Columbus Cole to be involved with the Japanese was because of his strong religious beliefs. Cole was an active Methodist and helped to build Marcola’s Methodist church. (61) He supported missionaries to Asia. Methodist churches were very active in Japan, where they were mostly welcomed.

Artist Maude Kerns Teaches in Mohawk

Maude Kerns, an 1899 graduate of the University of Oregon, taught at the McGowan School, about two miles from Ping Yang. (62) Kerns was later acclaimed for her work with Japanese art. She may also be the “Miss Kerns” in a news story (below) who taught at Ping Yang.

Maude Kerns, an 1899 graduate of the University of Oregon, taught at the McGowan School, about two miles from Ping Yang. (62) Kerns was later acclaimed for her work with Japanese art. She may also be the “Miss Kerns” in a news story (below) who taught at Ping Yang.

The name of Ping Yang must have fascinated her. She was a Methodist at this time in her life. One of her early portraits was of a Methodist minister in Eugene. [2] Maude had a sister, Edith, who also taught school. It’s possible that Edith was teaching at Ping Yang – or perhaps Maude transferred. It seems like the paper below would have given Edith’s full name if she were a new teacher.

Two news stories from April 1901 by different people with very different points of view describe the growing tensions. On April 20, a resident writes: “Ping Yang school house needs a coat of paint badly. Miss Kerns is teaching the Ping Yang school.”

“We have got a woman preacher at Ping Yang. Ping Yang is badly in need of a little missionary work. Mrs. Hickman of Salt Lake, preached at Ping Yang yesterday to a full house.”

The writer ends on a military tone with “Everything quiet at Ping Yang at present.” It is signed by someone calling themselves a “Ping Yanger.” (64)

A week later, on April 27, a writer called “Hay Seed” responds to Ping Yanger. He or she writes to correct misinformation in the earlier item.

“Mrs. Hickman of Parson’s Creek will preach at Ping Yang the third Sunday in May. The party that spoke of Ping Yang needing a missionary is off. Ping Yang don’t need a missionary, but the people that live around Ping Yang do, and we hope they may be able to have one. Mr. Mulkey is quite sick at his home but is improving some.” (65)

It may be that the “woman preacher,” Mrs. Hickman, was an evangelist and missionary of the Free Methodist church. There was a Free Methodist gathering near Ping Yang at the Parson Creek School, where Mrs. Hickman also preached. (66)

Clearly a tug of war was happening over the school, with religion now added to the mix. The Ping Yang School was destroyed by the third and final bomb less than three months later in July, 1901. (67)

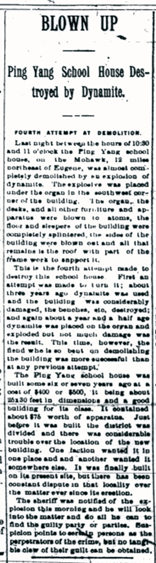

BLOWN UP

Ping Yang School House Destroyed by Dynamite

Fourth Attempt at Demolition

“Last night between the hours of 10:30 and 11:00 o’clock the Ping Yang schoolhouse on the Mohawk, 12 miles northeast of Eugene, was almost completely demolished by an explosion of dynamite. The explosive was placed under the organ in the southwest corner of the building. The organ, the desks, and other furniture and apparatus were blown to atoms, the floor and sleepers of the building were completely splintered, the sides of the building were blown out and all that remains is the roof with part of the framework to support it.

This is the fourth attempt made to destroy this schoolhouse. First an attempt was made to burn it; about three years ago dynamite was used and the building was considerably damaged, the benches, etc., destroyed, and again about a year and a half ago dynamite was placed on the organ and exploded but not much damage was the result.

This time, however, the fiend who is so bent on demolishing the building was more successful than at any previous attempt. The sheriff was notified of the explosion this morning and he will look into the matter and do all he can to find the guilty party or parties. Suspicion points to certain persons.”

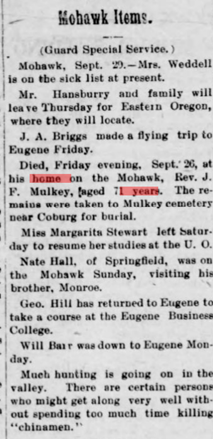

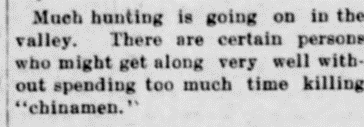

1903 – “Killing Chinamen” – Rev. Mulkey Dies

Reverend J.F. Mulkey died in 1903 at the age of seventy-one. Perhaps the strain of the fight to save the school took its toll on the old minister. The Mohawk news story reporting his death ends with an odd note, perhaps referring to Huddleston and his followers, although no individuals are named.

“there are some people who would get along very well without spending too much time killing “chinamen.” (68)

“there are some people who would get along very well without spending too much time killing “chinamen.” (68)

This sentence from October 3, 1903 confirms Claud Hammitt‘s story. Racial slurs were hurled at Rev. Mulkey and the school.

What happened to Maeda and Yoshihara after they left the Mohawk Valley is not known for certain. They did return to Japan, taking what they learned. Maeda wrote letters to the Hayden family until World War Two. (69)

Joe Huddleston lived until 1917 when he died after a stroke. (70) In one of Oregon’s most ironic twists of fate, the man who reportedly disliked school bells and student’s noise is now buried in the Pioneer Cemetery overlooking the University of Oregon, not far from the Asian and Pacific Studies office on busy 18th Avenue and University Street.

“Everything Quiet at Ping Yang at Present”

Why We Need to Remember Embarrassing History

The Ping Yang School bombings and the reasons for them have largely faded from Oregon’s memory. Some have asked “Why bring up this embarrassing history?”

The answer is that this history happened to real people. They deserve their stories to be told and their contributions remembered.

The Ping Yang School bombings remain one of Oregon’s largest unsolved crimes. It is small justice to research its history and document what happened.

Over the years several objections have been raised to this article. Joe Huddleston still has his supporters who see him as a unique individual. They reject Claud Hammitt’s portrayal of him. But Hammitt knew “Ole Joe” almost all his life – and often hauled supplies from town for him. His articles show that he mostly admired Joe Huddleston.

The hard work of Asians helped open the West and created countless fortunes. Their labor built the network of roads and railroads that made Oregon’s logging and mining industries grow and prosper. Yet they often did not get to share that prosperity. They usually had to leave communities shortly after doing backbreaking labor.

The courageous stories of educators like Maude Kerns, Ella Hayden, the Stafford and Spores families and others can still inspire us today. It is hard to overestimate the dedication these pioneer educators had.

Imagine being the teacher who had to step around a hole in the floor that was caused by a bomb, maybe by some of your own students. They were heroes to remember.

References & Further Reading

[1] Eugene Weekly Guard July-20-1901, “Blown Up” – the 3rd, bombing – reprint from July 15 Daily Guard

[2] Albany Democrat, May 04, 1900, “The Mohawk Road” – 150 of the railroad men are Italians or Japanese

[3] Mohawk Valley named by Jacob Spores.

[4] A History of the Mohawk Valley and Early Lumbering, book by Louis Polly 1984 P. 40

[6] Mohawk Elementary School Dedication Program 4-14-1964, Four school districts & boundary dispute

[7] Eugene City Guard. April 13, 1895, “School Ma’ams” – Miss Rhetta Smith Teaching Ping Yang School

[8] The Dalles Times-Mountaineer. April 27, 1895 – Ping Yang School demolished (First Bombing)

[9] The State Rights Democrat, May 03, 1895 – “School House Blown Up” (First Bombing)

[11] Maude Irvine Kerns (1876-1965). A biography by Barbara Zentner was published by the Maude Kerns Art Center in 1988. Pages 39-43. It briefly covers her early teaching years in rural schools and does an excellent job of documenting her importance in bringing Asian artwork to America.

[12] The West Magazine, April 1966, Page 64, “The Boxers versus the Highbinders” by Claud Hammitt

[13] The State Rights Democrat, May 03, 1895 – “School House Blown Up” – The First Bombing

[14] Eugene Weekly Guard 7-20-1901 “Ping Yang School House Destroyed by Dynamite” (3rd & final bomb)

[15] Eugene Register Guard 6-7-1963 “School Built in 1909 To Close” by Don Bishoff

[16] Eugene Weekly Guard 7-20-1901 Page 1. “Ping Yang School House Destroyed”

[19] Florence Oregon News. May 3, 1895. Page 1. “Blown Up.” (the 1st bombing)

[21] Springfield News, June 10, 1963. “Dynamited Organ Part of Mohawk History,” By Mrs. Marion Stafford

[22] Eugene Register Guard June-7-1963 “School Built in 1909 To Close” by Don Bishoff

[23] The West Magazine, April 1966 – Claud Hammitt – P. 33 – Joe Huddleston used dynamite for fishing

[24] Mohawk Items, Eugene City Guard, March 29, 1884 – boys carry deadly weapons for certain parties

[25] Eugene Weekly Guard, 4-13-1901, “Mohawk Items”. Railroad renames community for child, Donna Jackson

[26] The Eugene Weekly Guard., January 12, 1901 – “Change of Name” Railroad changes Isabel to Marcola

[27] Ping Yang Band photograph dated 6-13-1914. Curtis Irish Collection – the band organized years before

[28] Lane County Historian, Fall 1970 – Claud Hammitt, P. 58 – Hammitt School also known as Ping Yang School

[29] The West Magazine, April 1966, Page 64. “The Boxers versus the Highbinders” by Claud Hammitt

[30] On the Great Highway. By James Creelman, Originally printed in 1901, reprinted online by Cardinal Books. Creelman’s 1894 article “The Storming of Ping Yang” – possible source for the name of the Ping Yang School.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Florence Oregon Newspaper. May 3, 1895. Page 1. “Blown Up.” (see other 1895 bombing articles)

[33] Weekly Oregon Statesman., January 09, 1900 – Railroad Briefs. “negroes” and “Japs” arrived to work

[34] Daily Eugene Guard, March 26, 1900 – “White Men Quit” – Reprint from Junction City Times

[35] Eugene Weekly Guard., July 21, 1900, Nearly Impossible to Get Tracklayers

[36] University of Idaho, 1896, “Meiji Foreign Office Report on Idaho,” edited by Ronald L. James

[37] Eugene City Guard, January 14, 1899 – Lane County Leases the Mohawk River for 90 Years

[39] Wendling, Oregon Logging Camps 1898-1945 by Louis Polley, Polly Publishing, 1989, Pages 2-5

[40] The West Magazine, April 1966, Page 33. “The Boxers versus the Highbinders” by Claud Hammitt

[41] Mark Twain; speech at Berkeley Lyceum, NY. Nov. 23, 1900

[42] The West Magazine, April 1966, Page 33. by Claud Hammitt – Huddleston uses dynamite to fish

[43] Oregon Sentinel, Feb 12, 1881, Huddleston’s Tall Tale about Shooting 38 Deer with 37 Shots

[44] Eugene City Guard, July 18, 1885, Huddleston proposes to sell Blackberries for 12 ½ Cents a Gallon

[45] The West Magazine, April 1966, Page 33. by Claud Hammitt – Huddleston fighting with a woman

[46] The West Magazine, April 1966. P. 33 by Claud Hammitt – Huddleston helps mentally retarded neighbor

[47] The West Magazine, April 1966, P. 33 & 64. by Claud Hammitt – Mulkey, a “Chinaman” & “Highbinder”

[48] Pioneer History, Churches of Christ in the Pacific Northwest, http://ncbible.org/nwh/orhistmenu.html

[49] The West Magazine, April 1966, Page 64. Claud Hammitt – Mulkey, a sawed-off man with a long beard

[50] Daily Eugene Guard 4-21-1900, “Mohawk Branch – Sixty Japs Coming”

[51] Albany Democrat, May 4, 1900, “Mohawk Road” – 150 of the men are Italians and Japanese

[52] The Eugene City guard., April 07, 1900 – “Workmen Are Without Funds and Destitute”

[53] The Eugene City guard., April 07, 1900 – “A Lien for Work” – Mohawk Railroad Workers Not Paid

[54] Author’s Interview with Jim Hayden, grandson of Charly Hayden, February 2005 – Photos from Ella Hayden

[56] Eugene City Guard, August 01, 1896 “Interesting Revival” Free Methodists at Ping Yang

[57] Eugene City Guard. June 20, 1896 – “Mohawk’s republican boss” – Huddleston makes Ping Yang Brandy

[58] Eugene City Guard, October 10, 1896 – Speakers for William Jennings Bryan at Ping Yang School

[59] In This Great Land of Freedom, by the Japanese American Museum, 1993, Page 10

[60] “A History of the Mohawk Valley and Early Lumbering,” Videotape by Louis Polley, Marcola Oregon 1991

[61] A History of the Mohawk Valley and Early Lumbering, by Louis Polly – 1984 – Page 41

[62] Daily Eugene Guard. 4-10-1901 – Mohawk Items – Maude Kerns teaching at the McGowan School

[63] Maude Irvine Kerns (1876-1965). A biography by Barbara Zentner for the Maude Kerns Art Center, 1988, Pg 14

[65] Eugene Weekly Guard 4-27-1901 – Mohawk Items by Hay Seed – Mulkey is quite sick

[66] Daily Eugene Guard, 4-10-1901, “Mohawk Items”. Free Methodists meeting at Parson Creek School

[68] Eugene Weekly Guard., October 03, 1903 – Rev. Mulkey dies – “killing Chinamen”

[69] Author’s Conversation with Jim Hayden, grandson of Charly Hayden, February 2005

[70] Springfield News, 11-26-1917, “Pioneer Resident Dies” (Joe Huddleston obituary)

Many Thanks to Dr. Lynne Anderson & Mr. Curtis Irish

None of this research would have been gathered without the support of Dr. Lynne Anderson of the University of Oregon. Much of this material was originally collected for the Opal Whiteley Diary Project. Opal Whiteley was an Oregon writer who lived in the Marcola area as a child, after the final bombing. Read about her at www.opalnet.org

This article contains many news reports from the bombings. You can read these historic news stories at their online links. However, most of my information would not exist without the research and photos of the late Curtis Irish (d. 2021) of Marcola, Oregon.

Curtis Irish collected over 10,000 photographs of the Mohawk Valley and hundreds of newspaper articles. He was also an important mentor to this writer and other researchers. Discover his pictures at Flicker https://www.flickr.com/photos/36241830@N06

You can also see a video of how I met Mr. Irish in a graveyard and how he changed my life. Maybe his story will inspire you too. How I Met Curtis Irish in a Graveyard

Researchers like Debra Monsive, Louis Polley, and Jim Hayden, the grandson of Charly Hayden, provided rare photographs and news articles of the Japanese people who lived in the Mohawk Valley. We are all indebted to community historians who preserve history.

Also, many thanks to the Springfield History Museum and Lane County History Museum.

Browse Photos and News Items (and more) in this Article:

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1-8pAETLBPaYGFA3O_13ZxSQ0dGXCwnP9?usp=sharing

Here is a picture of me in 1976 at age 25 as a “Gandydancer” building railroads. Both my grandfathers did railroad work. It was brutally hard labor, and I was a strong young man.

I am also deeply grateful to the annual Oregon Asian Celebration which has encouraged me to do exhibits for over 20 years.

Did you know that north of Ping Yang there was a Japanese colony at today’s Shotgun Creek Recreation Area? Read about it and other stories at my website. Below is a driving tour to Ping Yang. It is a nice afternoon drive.

June 1900 US Census – 50 Japanese & Many Italians

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1_SRx6bgQV0jsQiAkZgpeFfzZNdLM3rTs/view?usp=drive_link

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1–raLFQoZZYSkpABEWZUjQVKTaBZW7Ux/view?usp=drive_link

50 Japanese Immigrants on 1900 Mohawk Census

Mohawk had About 700 People in 1900; Note the large number of Italians & Greeks

Research by Debra Monsive

Cottage Grove Oregon Genealogical Society

There are many other news items about Ping Yang. You can search for them at this link of Historic Oregon Newspapers: http://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/

If You want to Learn More or have Stories or Photos to Share Contact Me